Why Pathological Demand Avoidance?

Mar 15, 2024

“How would you respond to the viewpoint that the term ‘Pathological Demand Avoidance’ is a pathologizing term and frames the PDA neurotype through a behavioral lens?”

I was interviewed this week by an academic conducting research on PDA in the educational setting.

I sort of chuckled because I have been asked this before. And I agree with that viewpoint in many ways. It’s a deeply imperfect term.

In fact, in my work with parents – especially when they are developing the skills to guide their child or teen to a healthy self-concept and identity – I deliberately use the acronym PDA, without saying “pathological demand avoidance,” to give an openness around the label. I also often encourage them to experiment with dropping labels altogether and starting from scratch, especially if the child or teen has a negative connotation with a previous diagnosis.

Instead, I encourage parents to practice making affirming observations that would resonate with their child or teen.

Wow, your brain works so much faster than mine!

I can’t believe you could see that bird so far away! My eyes aren’t nearly as sharp as yours.

Animals feel so safe with you. You truly have a special connection that others don’t have.

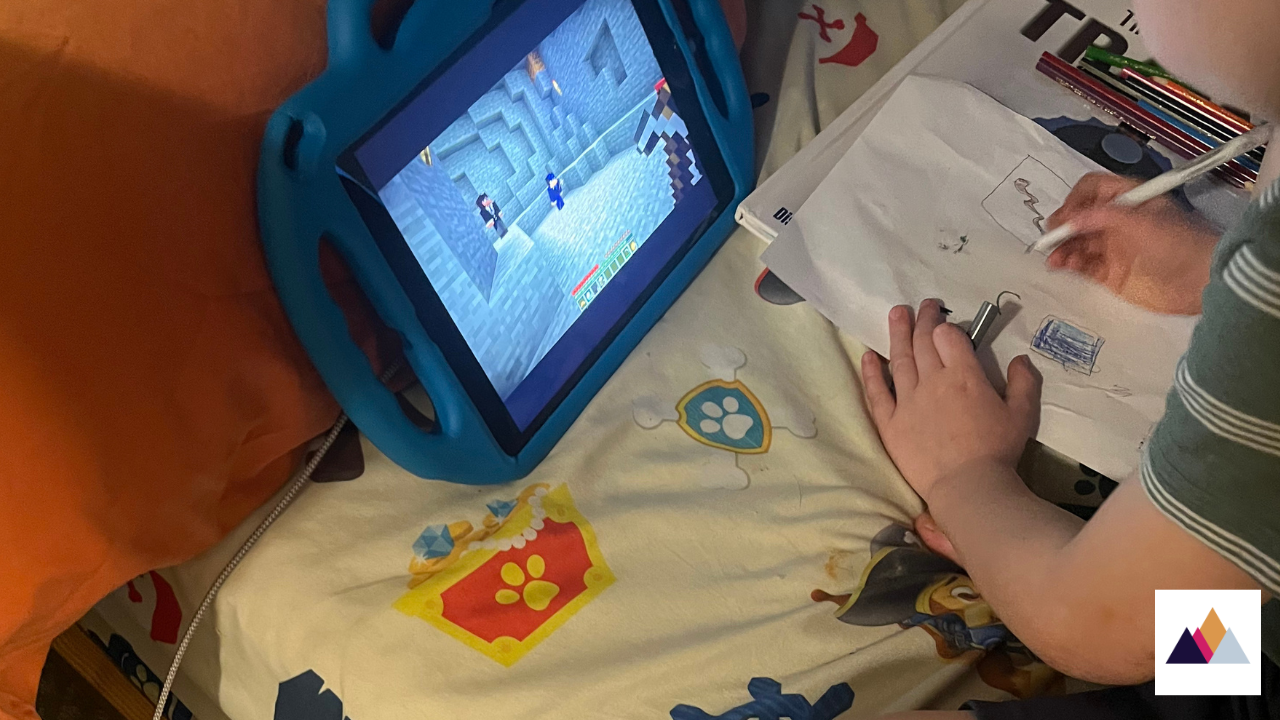

It’s amazing how you know how to build so fast in Minecraft.

These are small seeds planted, gently and patiently. The parent then observes –

How does my child respond to these observations?

Are they activated or do they seem to like these affirming sentences?

We then slowly, slowly practice bridging the affirmations with a sense of belonging. It is at the very end of this process we offer potential identity labels. It might take months to get to the point where we ever “strew” the word “PDA” and then explain what it might stand for – “pervasive drive for autonomy” or “protective demand avoidance”.

I encourage parents to add, “Or we don’t have to call it anything at all.”

I take this approach because I have seen it result in positive self-concepts for so many of the PDA children and teens in the families I’ve worked with.

However, outside of my work with parents, I do use the term “Pathological Demand Avoidance” for strategic reasons – I want PDA recognized on an institutional level and in the Diagnostic Statistical Manual of Disorders.

And what I know from my “past life” working 15 years in research and policy is how important it is to build on an existing canon of research when seeking institutional recognition. And the existing canon on PDA – albeit imperfect and limited – uses the term “Pathological Demand Avoidance.”

In order for PDA to be recognized officially by doctors, policymakers, academics and others leading our institutions, there has to be evidence-based, empirical and peer-reviewed research that builds on the existing literature on the topic. And this is what I am working on with the University of Michigan School of Medicine.

This work takes a long time. It is tedious. I am not compensated for it. And it likely won’t benefit my son’s generation in the way it will future generations.

But I believe this is a critical way to bring about structural change and supports – diagnostic, logistical and financial – for countless PDA children and teens, and especially those in low-income families and families of color, or in foster care.

The constraints these families, children and teens face can be significant:

- PDA children of color are less likely to be viewed through a disability lens and more likely to be fed into the school-to-prison pipeline.

- Low-income families often cannot afford therapies and supports that are not ABA-centered.

- Both groups may face more difficulty advocating for the legal rights of their children in public schools.

This is one of the reasons that in my Paradigm Shift Program we practice Cost-Benefit Decision Making Within Constraints. We work to radically accept the current realities each family faces, and that those realities – no matter how unjust – may impact the decisions and accommodations the parents choose in raising their PDA children.

And we do this within a programmatic culture of non-judgement. Every single parent in the program is there because they want to help their child and their family find peace. We cheer each other’s wins and empathize with each other’s challenges.

In the meanwhile, some of us are also working outside the program to change our society, and doing so in whatever way we are best equipped (for me that is empirical research!). Others may need to focus singularly on stabilizing their families, but I also believe down the road that will create tremendous ripple effects for the greater good.

No matter how “small” your work may seem currently – sitting on the couch signaling safety to your teen in burnout while they watch their ipad – I believe it is heroic, and life-saving.

Have a good weekend everyone.

Want my blog posts in your inbox?

Most weeks we send two emails. You can unsubscribe any time.